Part 3: Inside the OR—What Really Happens During a Knee Replacement (And Why It’s Not Just a “Swap”)

Jul 04, 2025

When people think about knee replacement surgery, they often picture something simple and clean—like removing an old part and installing a new one. But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

This isn’t an oil change. It’s not an upgrade. It’s a major structural overhaul—and once it’s done, there’s no going back.

Let me tell you how I know.

After COVID upended life as we knew it, I made the tough decision to close my acupuncture and massage practice in Denver, Colorado. Like many healthcare providers, I had to pivot. So I turned toward a field where my deep background in orthopedics and anatomy could thrive—and I became a medical sales rep in orthopedics.

For several years, I worked directly in the OR with trauma and joint surgeons—shoulder to shoulder, mask to mask. I stood behind the sterile field, guiding scrub techs on what to hand the surgeon next, double-checking implant compatibility, confirming X-ray alignment, and ensuring the correct size and style of hardware was chosen.

And yes, I saw a lot of knee replacements. And hips. And shoulders. I saw what worked, what didn’t, and what most patients never get to see or hear.

So let’s go behind the scenes. Here’s what really happens when you get your knee replaced—and why it’s far more complex than most people are told.

Step One: Say Goodbye to Your Natural Joint

This is not a cleanup job. When you get a total knee replacement, the surgeon uses a precision-guided saw to cut away the surfaces of your femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), and sometimes the back of your patella (kneecap). The ends of these bones are shaved into flat platforms so they can receive the implant.

That means your natural joint—cartilage, contours, and all—is permanently removed.

Once that bone is gone, it’s gone for good. This is irreversible.

And that’s the part most patients don’t fully grasp: a total knee replacement isn’t adding something—it’s taking away your original design and replacing it with hardware. Functional? Sometimes. Natural? Never.

Step Two: Metal and Plastic Become Your New Anatomy

After the bones are prepped, the surgeon fits custom metal caps over the femur and tibia, and a medical-grade plastic spacer is inserted in between to act as your new “cartilage.”

This becomes your new joint surface—metal-on-plastic instead of bone-on-bone. Depending on the implant system, these components are either cemented or press-fit into place so that your bone can grow around them for stability.

Here’s where it gets tricky: most implants are designed symmetrically, meaning they don’t replicate the natural roll, glide, and rotation that your real knee used to perform. Your natural knee joint is not symmetrical—the medial (inner) side of your femur is shaped differently than the lateral (outer) side. That’s what allows for proper “roll-back” in deep flexion like kneeling, squatting, or sitting on your heels.

Once that natural shape is removed, most standard implants can’t fully replicate those motions—so the result may feel stiff, awkward, or “not quite right” even when pain is reduced.

A Step Toward Better: Ergonomic Implants Like Smith & Nephew’s

Now, not all implants are created equal. Some companies—like Smith & Nephew, the one I represented in the OR—have developed more ergonomic, anatomically inspired implant systems, such as the Journey II BCS.

These are designed to better mimic the natural asymmetry of the femur, with improved roll-back, more natural flexion, and potentially better overall movement.

The challenge? Most patients have no idea what implant they’re getting, and many surgeons don’t go into detail about the system they’re using.

You should absolutely feel empowered to ask:

“Which implant system are you using, and why?”

“Does it support natural motion or deep flexion?”

Because while no implant will ever be as perfect as your original joint, the design does matter—and so does the surgeon’s experience using it.

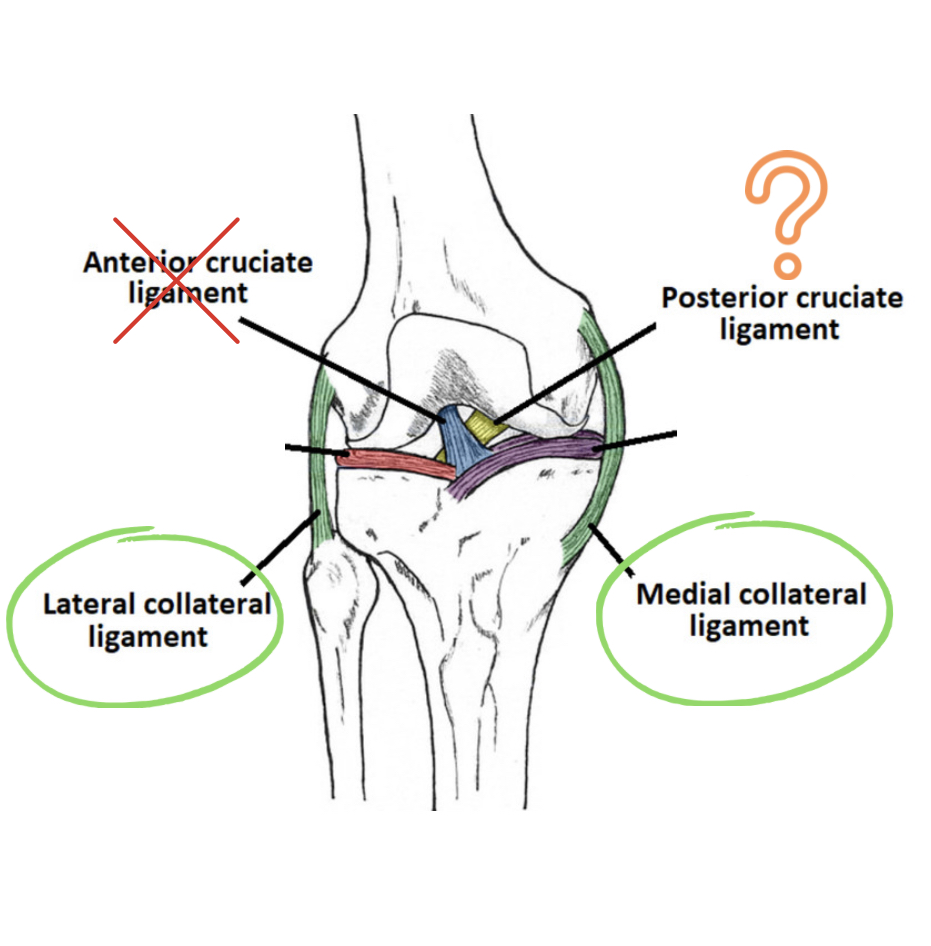

Step Three: Ligament Balancing (A.K.A. Soft Tissue Math)

Here’s the part where the surgeon becomes part-engineer, part-artist. After the implant is placed, they assess the surrounding ligaments—particularly the medial and lateral collateral ligaments—to make sure the new joint is balanced.

Too tight? You’ll feel stiff. Too loose? You might feel unstable. In some cases, the surgeon has to release or cut a ligament to achieve proper alignment.

That’s right—sometimes your ligaments are sacrificed to make the hardware fit. This affects long-term function, proprioception (awareness of the position and movement of the body), and movement confidence.

Step Four: Closure… and the Long Journey Back

After the joint is balanced and aligned, the incision is closed layer by layer. Surgery typically lasts 1–2 hours. But here’s the truth: the real work starts after you leave the OR.

You’ll be on your feet within a day or two (thanks to aggressive rehab protocols), but the process of regaining strength, range of motion, and natural movement takes months to years. And in many cases, you’ll never regain the same ease of motion you had before—even if pain improves.

For younger or more active patients, this can be incredibly frustrating. You can walk, but maybe not hike. You can climb stairs, but not kneel. The knee is functional—but it may never feel like yours again.

What You’re Not Always Told in That Pre-Surgical Consult

Surgeons are busy, and sometimes brutally efficient. But here’s what often gets skipped in that 15-minute visit before you get booked for surgery:

-

Your new knee won’t feel like your old one. It’s mechanical, not biological.

-

You may experience permanent numbness around the incision.

-

Deep bending like kneeling, squatting, or sitting cross-legged may be permanently limited.

-

Revisions (redoing a replacement) are more difficult and often less successful.

-

Your outcome depends heavily on your pre-op health, strength, inflammation levels, and commitment to post-op rehab.

This is why I’m so passionate about prevention, prehab, and patient education. There’s so much more to this process than a before-and-after X-ray.

Should You Still Do It?

For some people—those with advanced deformity, intractable pain, and bone-on-bone arthritis who’ve exhausted conservative options—yes, a total knee replacement can be life-changing.

But for others—especially those in their 40s, 50s, or early 60s—it’s worth exploring every other option first. Because once that joint is gone, you can’t get it back.

In Part 4, we’ll talk about the questions most people wish they had asked before saying yes to surgery—and the things you should absolutely consider before going bionic.

Until then…

Keep moving, eat something green, and question anything that sounds like a quick fix.

Chow! Chow!

Note: Mention of Smith & Nephew reflects my personal experience in the OR and is not a paid promotion or endorsement. I do not align with or promote any specific orthopedic brand.